|

...introduction

continued;

We are apt to think, in reading of the times in which

David lived, quickening with the new birth of republican ideas, and

ripe for revolt against feudal forms and usages, that he painted the

Horatii and his other so-called antiques, out of sympathy with the spirit

of the age. David was, as his political conduct showed, an enthusiast

for republican ideas, and in the case of "The Sabines," "The

Death of Socrates," "Leonidas at Thermopylae" and "Brutus"

his feelings may have had something to do with his selection of the

subjects. But it was not so with "The Horatii." The subject

of this picture was dictated by Government in strict accordance with

rules established some years previously, when M. de Marigny was appointed

Minister of the Fine Arts, or as the office was then called, Director

General of the Royal Buildings. De Marigny found the arts in a very

low condition when he came to his post, and he conceived a plan to elevate

and improve them, which plan he not only carried out for himself but

established so firmly that it exists in force and but little modified

to-day. Pictures, statues, works of art of every kind ordered by the

Government for the public buildings; the palaces, churches and offices,

were looked upon as adjuncts and appendages to the architecture and

decoration of the building, not as works of art, independent of their

surroundings. Accordingly their price, dimensions, subjects, everything,

in short, that pertained to them was limited and defined by authority

in the most precise and formal way. When, therefore, after David had

been received into the Academy, the government decided to give him a

commission for a picture, it was altogether in the order of things that

the subject of the picture should be commanded at the same time. It

would probably have puzzled the then Director, M. d'Angivilliers, who

gave the commission, to account for the choice of a subject in this

case. For whatever reason, the subject was given to David, and he accepted

it without demur. He had already made his oblation to antiquity in his

Academy picture, "Andromache mourning the Death of Hector,"

and as he certainly could have had no reason personal to himself, nor,

for that matter, personal to anybody, for selecting such a theme, it

would have ill become him to stick at accepting the one dictated to

him by the Government. It is not likely that he felt any objection.

He at once set about the task imposed, glad of the honor done him, and

when he had once conceived the disposition of the personages of his

picture, he decided to go to Rome to paint the picture there, in the

very place where the event he was to depict had occurred. He left Paris

in 1783, accompanied by his young friend and pupil, J.G. Drouais, who,

when only seventeen years old, had carried away the Grand Prize of Rome,

and who remained closely attached to his master until his death in 1788,

at the age of twenty-five. He was also accompanied by his friend Giraud,

a young sculptor, a man of ample means, who went with him for no other

purpose than to get out of the Academic ruts, and to bring himself into

intimate, and, so to speak, personal relation with the true antique

art. The story of Giraud is interesting as an indication of the way

in which this new-found love of classic art took possession of some

among the more ardent youthful minds. During the three years he was

in Rome, he almost lived in the Vatican, in order to banish from his

eyes the very sight of the art that was corrupting the taste of his

time. He formed a collection, very extensive for that day, of plaster-casts

from the antique sculpture, then a very costly undertaking; and so great

was his eagerness to obtain these copies that, as he used to relate,

after having obtained from the authorities with the greatest difficulty

the permission to mould the Apollo Belvidere he was obliged to give

the keeper of the Vatican Museum six silver dishes and a large silver

spoon to secure his interest in the matter!

When the picture of the Horatii was completed, it

was exhibited in Rome, and was received with enthusiastic expressions

of approval. The artist was serenaded by the younger artists; sonnets

without number were written in his honor, since to an Italian it is

as natural to write sonnets as it is to eat macaroni, and in addition,

the steps of the building where the picture was exhibited were strewn

with laurel, and the hall itself hung with garlands. Pompeo Battoni,

at that time nearly eighty years old, the venerable head of the artist-world

in Rome, and called the reviver of modern art, visited the picture with

his pupils, and not only lavished the warmest praises upon the work,

but strongly urged David to remain in Rome and establish a school there.

David, however, resisted all this solicitation, and declined the offers

he received to sell the picture in Rome, since he considered it already

the property of his own Government, and he returned to France, where

he exhibited the work in the Salon of 1785.

It was received by the public and by the artists

with even greater enthusiasm than had attended the exhibition of it

in Rome. No doubt, that previous success had much to do with this reception,

and perhaps, as Delecluze suggests, the extraordinary fact of David's

pupil, Drouais, winning the Prize of Rome at so early an age the year

before, may have added to the enthusiasm for the master, who was always

greatly beloved and admired by his scholars.

It was pointed out by the critics that the composition was not well

balanced either artistically or morally, since there were, in fact,

two pictures on one canvas: the group of women, the mother and sisters

of the Horatii, with the children who take refuge in their mother's

lap, frightened by the clash of arms and the resounding voices of the

warriors; and the group of the old father administering the oath to

his sons not to return from the fight unless victorious. Owing to this

division, the interest of the spectator could not be united, but must

come and go from one to the other of these two groups, so essentially

different in character and intention.

David himself admitted, in later years, the justice of much that was

said in criticism of this picture; criticism that was due to the study

then making in France and in Germany of the principles that governed

the antique art. He settled for himself the question of the composition,

by frankly admitting (this was in 1796) that it was theatrical; he found

the drawing mean, the anatomical details too much studied. "This

work," he said, "reflects the taste of the Roman art, the

only art with which I concerned myself during my stay in Italy. Ah,

if I could but begin my studies again, now, when antique art is so much

better known and studied, I could go straight to my aim. I should not

have to waste the time I did, in cutting my own road. Yet, after all,"

he added, with a noble pride, speaking to the young men who surrounded

him, "there is force in that picture, and the group of the Horatii

is one that I shall never be ashamed of."

David followed up the success of the Horatii with other classic subjects,

not one of which had any more reason for being than the one that led

the list. But it would seem that the artist seldom originated the subjects

that he painted, and as that of the Horatii had been dictated to him

by M. de Marigny, so it was M. Trudaine, who now asked him to paint

"Socrates surrounded by his Disciples, receiving the Cup of Hemlock

from the hands of the Messenger of the Eleven." The "literary"

character of all these official subjects is best expressed in the amplitude

of their titles. In 1788, David essayed, in his "Paris and Helen,"

painted for the Count d'Artois, afterward Charles X., a subject foreign

alike to his taste and his ability. He could not put passion into his

pictures, nor had he the natural bent for grace of movement, or beauty

of line, in which others of his contemporaries, his pupils, and his

rivals, excelled. Yet, it must not be forgotten, that on occasion, as

is seen in his sketch for the portrait of Madame Recamier, he could

equal, if not surpass, the best in that direction. But, in general,

he was not at home in this field, and seldom ventured to work in it.

Yet in his later years, at the age of sixty-eight, he painted two pictures,

"Love parting from Psyche," and "Mars disarmed by Venus,"

which excited a lively interest, and are certainly, so far as their

execution is concerned, equal to any of his works produced earlier in

his career. The picture which followed the "Death of Socrates,"

"Brutus returning to his Home after condemning his Sons to Death,"

was commissioned by Louis XVI. In 1789; a sinister subject to be selected

in such a troubled time. Like "The Oath of the Horatii," the

theme would seem to have been taken at random, yet that it appealed

to something in the state of the public mind at the time, is shown by

the enthusiasm it excited, and by the influence it had upon the fashions

in dress and furniture, strengthening the movement already set on foot

by the picture of the Horatii. The head of Brutus, copied from the well-known

bust in the Capitoline Museum, set a fashion of wearing the hair a la

Brutus, and according to one authority, gave the last blow to the wearing

of powder. The furniture of the house of Brutus was copied from objects

designed by David himself from hints found in the antique vases, and

the bas-reliefs he had seen in Rome. What he had already done in this

way to influence the public taste by the "Horatii" and the

"Socrates," was greatly strengthened by the appearance of

the "Brutus," a picture that dealt with a story more familiar

to the public, and capable of a more objective treatment than either

of its predecessors.

As we have only to deal here with David the artist, we shall merely

allude to the fact that as a natural result of his enthusiasm for republican

ideas and for the principles which he imagined to be represented in

the life of antique Greece and Rome, he was carried away by the Revolution,

and took an active and extraordinary part in the political events of

his time. Shortly after painting the "Brutus" at the command

of the King, a commission which led to his receiving orders for portraits

from many persons in the highest ranks of society, David, in 1790, accepted

from the Constituent Assembly the commission to paint "Le Serment

du Jeu de Paume" - the Members of the Assembly, met in the Hall

of the Tennis Club at Versailles, taking the Oath to support the Constitution.

The abandoned Church of the Feuillant Order, near the Tuileries, was

given David for a studio, and a public subscription was opened to pay

the expenses of the work. A year later - so swift was the march of the

Revolution - and the Convention was dissolved; the picture, for which

David, assisted by his pupil Gerard, had made the sketch, was carried

no further toward completion. It remained in the Church where it was

begun, until Bonaparte, become Emperor, caused that quarter of the city

to be destroyed in order to make room for the Rue de la Paix and the

Rue de Rivoli. The canvas was then removed to the lumber-room of the

Louvre and was forgotten there until about twenty years ago, when it

was hung in one of the smaller rooms of the Louvre, and made accessible

to the public. It is of interest only as a curiosity. David drew the

figures nude, before clothing them in the costumes of their time, but

he left them in outline merely, and had nearly finished the heads, so

that, as they stand with outstretched arms, in action strongly recalling

that of the Horatii, there is something ghostly in the apparition; it

is the resurrection of a time, of ideas, of persons long ago passed

out of the world of men.

In 1793, David, with the majority of the Convention, voted for the death

of the King. In July of the same year Marat was assassinated by Charlotte

Corday; David, who had been the friend of Marat, and had defended him

when he was attacked in the Convention, was struck with horror at his

death; he rushed to the house, and made on the spot a sketch of the

victim as he still lay in the bath, and a little later he moulded a

mask of his face to aid him in painting the picture ordered by the Convention

and now in the Louvre.

It is not our province to comment on these perversions of a nature that

had in it so much that was worthy of respect as is to be found in David.

Looked at abstractly, as art merely, it is to be said that David's "Marat,"

by the simplicity of its composition, by its unity, and the strong impression

it conveys of a work sprung from deep feeling, is perhaps the picture

that will in the end by thought to represent him best. As is well known,

David had not to wait long before he was made to taste something of

the bitterness of the draught he and his party had prepared for others.

The fall of Robespierre carried with it the fall of David and his friends;

the artist was menaced with the guillotine, and it was with difficulty

that his life was saved; but he had learned his lesson, and from that

time he took no active part in the politics of his country. Yet so long

as he lived he was to suffer for the part he had taken in the Revolution,

nor did his later enthusiasm for Bonaparte, and the affection and favor

that the Emperor showed for him, lighten the punishment that was meted

out to him on the return of the monarchy. It was while Napoleon was

in power that David painted two other classic subjects that have taken

rank with the three we have already mentioned; the "Horatii,"

the "Socrates," and the "Brutus." These were the

"Sabines" and the "Thermopylae." The subject of

the former picture was the moment when the Sabine women, now become

mothers, rush in between the combatants - their own fathers, and brothers,

and their husbands - and holding up their children, implore that the

threatened conflict may be stayed. The picture, when finished, was exhibited

in one of the halls of the Louvre, and David, who up to this time had

received but little profit from the sale of his works, took a hint from

English customs, and charged a price for admission. The eagerness to

see the picture was great, and the receipts from the sale of tickets

amounted to twenty thousand francs; but although the public submitted

to the tax, David's action was generally blamed, and with some slight

and unimportant exceptions the experiment has never been repeated in

Paris.

The "Sabines"was followed by the "Thermopylae,"

or, as it is sometimes called, the "Leonidas," since the subject

is not the actual battle of Thermopylae, but represents Leonidas and his warriors

preparing themselves for the conflict. On the appearance of each of these pictures

criticism awakened anew, and the same objections, increasing with time,

made themselves heard, that had been aroused by the "Horatii"

and its immediate successors. David was reproached with the theatrical

grouping, the affinity of the treatment to the methods of sculpture

rather than of painting, and this, not merely in the general resemblance

of his pictures to painted bas-reliefs, but in such details as the designing

the horses without bridles, in conformity with the supposed practice

of the Greeks, as shown in the frieze of the Parthenon, and the direct

copying of the figure of Leonidas from a well-known antique gem. At

that time it had not been discovered that in the Greek sculpture many

details, such as the bits and bridles of the marble horses, spears in

the hands of warriors, and other things of the same general character,

were made of bronze and attached to the sculpture, and that their absence

in our time is due to the fact that they have been carried off as plunder

by conquerors or melted up for one purpose or another. As for the charge

of plagiarism, David paid little heed to it, declaring that such borrowings

savored of daring and presumption rather than of timidity, since nothing

is more dangerous for an artist than to appropriate types long familiar,

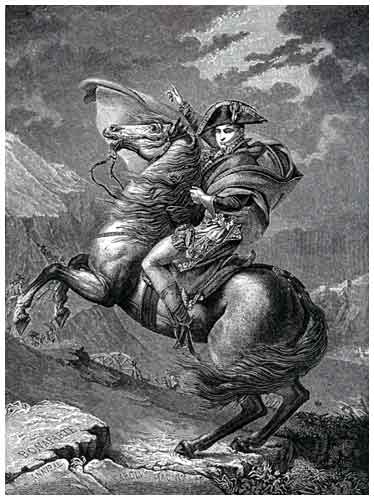

and, as it were, consecrated by time. The chief pictures that David

painted to illustrate the reign of Napoleon were the "Coronation,"

and the "Distribution of Standards to the Army on the Champ-de-Mars,"

with the Equestrian portrait of Napoleon as Consul, of which we have

already spoken. After the fall of Napoleon, David was exiled from France,

and went to Brussels, where he died in 1825. During his last years,

from 1816 to 1825, he led a tranquil and measurably happy life, surrounded

by his friends, and frequently visited by his pupils, than whom no artist

ever had more affectionate or devoted. His wife, too, who had been for

a time alienated by her husband's course in the time of the Revolution,

came to his side when she heard that he was in trouble, and cheered

his latest days with wifely sympathy and care. He died while correcting

a proof of the engraving which Laugier had made of his "Leonidas."

Lying in bed, and supported by his attendants, he indicated with his

cane the parts of the plate which called for correction. "Too black.

. . Too pale. . . Just here, the grading of the light is not well expressed.

Here, the touch is uncertain. . . And yet, the head of Leonidas is good,"

- his voice failed, the cane dropped from his hand, and he breathed

his last.

The pupils of David numbered among themselves some of the most distinguished

artists of their time. Delecluze gives, at the end of his book, a list

of no less than 296 names, and among these are two sculptors who are

among the glories of France - David d'Angers, so called from his birth-place,

to distinguish him from his master, and Rude, of whom we have already

spoken. Among the painters who owed their teaching to David, the most

famous were Ingres, Girodet de Trioson, Gerard, and Gros, men who in

their turn, two of them in especial, Ingres and Gros, had an influence

on the generation that followed them almost equal to that of David himself,

though not so exclusive, since, in their day, other influences came

in to dispute the supremacy of the ideas which David, by his strong

personality, aided by the events of his time, had imposed upon his generation.

continued...

|